As inflation soars and recession looms in Poland, a break from mortgage payments will be a much-needed reprieve for Jakub Rdzanek and his wife.

The couple have seen their monthly home loan bills soar more than 70 per cent since the start of the year, as the country’s central bank has raised interest rates to combat rocketing prices.

“Our mortgage has suddenly become terrifying,” said Rdzanek, who bought their Warsaw flat last August.

The Rdzaneks are not the only household breathing a sigh of relief after the Polish government placed a moratorium on mortgage repayments last Friday.

The move will allow borrowers to suspend payments for eight months, split between this year and next. But while the Polish government is granting mortgage holders a credit holiday, banks are warning that it will wipe out their profits.

Lenders also claim that the rightwing government is gifting borrowers the mortgage holiday to boost its chances of winning a national election next year. The outcome could hinge upon whether Poland’s economy manages to weather the double blow of soaring inflation and the war in Ukraine.

It is not just eastern Europe that is seeking to ease the pain; governments around the world are facing the challenge of curbing high inflation by raising interest rates, as the cost of living crisis casts a shadow over the global economy.

Banks have been a target for other governments. Hungary recently announced a €2bn windfall tax on lenders and energy companies, while Spain said it would tax banks €1.5bn a year. Romania is also considering relief from mortgage payments for households that are the hardest hit by inflation.

“This idea is obviously starting to catch on elsewhere, so it’s something we need to watch,” said Simon Nellis, managing director of European banks research at Citigroup. “This is clearly a concern for bank equity holders.”

Unlike the Romanian proposal, Poland’s policy is not means tested. Some Polish regulators had urged the government to limit the scope of the moratorium. “There are also rich people who do not need this exemption,” Adam Glapiński, governor of the National Bank of Poland, said at a news conference last month.

Glapiński also questioned whether the law went “in a different direction” from the central bank’s monetary tightening efforts. Poland raised its benchmark interest rate in July for the sixth consecutive month to 6.5 per cent, after inflation hit a 25-year-high.

Some bankers have even suggested the government has launched a crusade against them. Jarosław Kaczyński, the leader of the main government party, Law and Justice, recently proposed a windfall tax on banks that failed to pay enough interest on deposits.

Polish banks were on track to report strong earnings, but they are now estimating a combined cost of about 20bn zlotys ($4bn) if all eligible mortgage holders skip monthly payments. The moratorium applies only to mortgages contracted in zlotys.

Poland’s two largest banks, PKO and Pekao, which account for 40 per cent of the domestic mortgage market, will be the hardest hit by the change. But the Polish arms of foreign lenders Santander, ING, Commerzbank and BNP Paribas will also suffer.

Commerzbank anticipates that 60 to 80 per cent of the mortgage holders of its Polish subsidiary, mBank, will take the credit holiday. The bank is considering legal action against the Polish government. “Unfortunately, the new legislation in Poland causes considerable one-off burdens,” said Bettina Orlopp, Commerzbank’s chief financial officer.

Citi’s Nellis expects some banks to take the issue to court, despite the poor record of previous attempts to force governments to change policy on mortgages. “The government is getting involved and retroactively changing contracts, which looks a bit naughty,” he added.

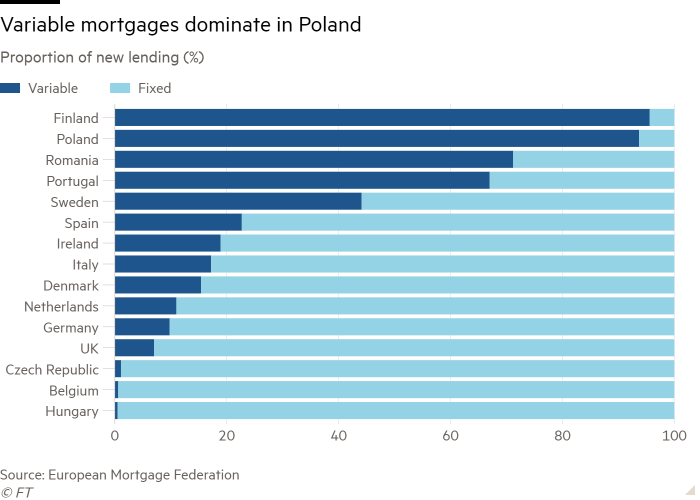

Poland’s housing market is highly exposed to rate fluctuations because the overwhelming majority of Polish mortgages carry a floating rather than a fixed rate. In Romania, variable mortgages represent more than 70 per cent of new lending, leading the government in Bucharest to propose mortgage holidays.

Some economists are warning that Poland’s credit holiday could prove counterproductive as monetary tightening already threatens to push the economy into a technical recession in coming quarters.

“Banks may become more selective in offering financing,” said Marcin Kujawski, senior economist at the Polish subsidiary of BNP Paribas. The moratorium, he warned, “may lead to tighter credit policies, as well as more entrenched inflation, which possibly could require more interest rate hikes than would otherwise be the case”.

In another move, the government is seeking a new interbank lending rate as early as January.

However, banks are warning against fast-tracking a reform of the Warsaw Interbank Offered Rate, similar to that undertaken to remove the scandal-tainted Libor rate, which took years to come into effect. BNP Paribas is among banks warning that changing Poland’s rate could lead to international lawsuits.

“This is a massive reform, it means repricing all the portfolios and also all the hedging instruments,” said Przemysław Paprotny, who leads the financial services practice of PwC in Poland. “We have to remember that Polish banks are hedging out the interest rate and forex risk — and this is contracted with international parties.”

Despite the uproar in the banking sector, Paprotny said the balance sheets of Polish banks were solid enough to withstand the moratorium. “We don’t foresee any dramatic situation that would call for discussions about immediate capital injections,” he said.

The Polish banking market is still entangled in a decade-long court battle over who should bear the cost for Polish homebuyers who opted for mortgages in Swiss francs in the early 2000s, when Switzerland had far lower rates than Poland. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the cost of these mortgages surged, in line with the Swiss franc’s appreciation against the zloty.

Agnieszka Accordi, an audit partner at PwC, said reviewing how borrowers finance their homes made sense in the context of Swiss mortgages. Poland, she said, should seek to “close the discussion about whether customers understand what they are paying for.”

When Rdzanek and his wife bought their Warsaw flat last summer, their real estate agent advised them to use a variable rate for their mortgage. “It’s a decision that I regret for sure,” Rdzanek said. The administration fees charged by his bank have also risen sharply in recent months.

Even at a time of intense political polarization in Poland, the moratorium was overwhelmingly approved in parliament, backed by a leftwing opposition that wants to share the credit for helping consumers rather than banks.